Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)

- 27 jun 2023

- 87 Min. de lectura

Updated: Apr 06, 2023

Overview

Practice Essentials

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is defined as illness caused by a novel coronavirus called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2; formerly called 2019-nCoV), which was first identified amid an outbreak of respiratory illness cases in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, China. [1] It was initially reported to the WHO on December 31, 2019. On January 30, 2020, the WHO declared the COVID-19 outbreak a global health emergency. [2, 3] On March 11, 2020, the WHO declared COVID-19 a global pandemic, its first such designation since declaring H1N1 influenza a pandemic in 2009. [4]

Illness caused by SARS-CoV-2 was termed COVID-19 by the WHO, the acronym derived from "coronavirus disease 2019." The name was chosen to avoid stigmatizing the virus's origins in terms of populations, geography, or animal associations. [5, 6] On February 11, 2020, the Coronavirus Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses issued a statement announcing an official designation for the novel virus: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). [7]

The CDC estimates that SARS-CoV-2 entered the United States in late January or early February 2020, establishing low-level community spread before being noticed. [8] Since that time, the United States has experienced widespread infections, with over 97.6 million reported cases and over 1,125,000 deaths reported as of March 29, 2023 as reported by the CDC COVID data tracker. According to the CDC, 75% of people who have died of the virus in the United States as of April 5, 2023 are aged 65 years or older. According to the New York Times, the CDC reports that 1 in 100 older Americans has died from the virus. For people younger than 65, the ratio is about 1 in 1,400.

On April 3, 2020, the CDC issued a recommendation that the general public, even those without symptoms, should begin wearing face coverings in public settings where social-distancing measures are difficult to maintain to abate the spread of COVID-19. [9]

The CDC had postulated that large numbers of patients could require medical care concurrently, resulting in overloaded public health and healthcare systems and, potentially, elevated rates of hospitalizations and deaths. The CDC advised that nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) are the most important response strategy for delaying viral spread and reducing disease impact. Unfortunately, these concerns have been proven accurate.

The feasibility and implications of suppression and mitigation strategies have been rigorously analyzed and are being encouraged or enforced by many governments to slow or halt viral transmission. Population-wide social distancing plus other interventions (eg, home self-isolation, school and business closures) are strongly advised. These policies may be required for long periods to avoid rebound viral transmission. [10]

As the United States is experiencing another surge of COVID-19 infections, the CDC has intensified its recommendations for transmission mitigation. They recommend all unvaccinated individuals wear masks in public indoor settings. On the basis of evidence regarding emerging variants of concern (See Virology), CDC recommends that persons who are fully vaccinated also wear masks in public indoor settings in areas with substantial or high transmission. Fully vaccinated individuals might consider wearing a mask in public indoor areas, regardless of transmission level, if they or someone in their home is immunocompromised, is at increased risk for severe disease, or is unvaccinated (including children younger than 12 years who are ineligible for vaccination). [11]

The CDC recommends physical distancing, avoiding nonessential indoor spaces, postponing travel until fully vaccinated, enhanced ventilation, and hand hygiene. [12, 13]

According to the CDC, individuals at high risk for infection include persons in areas with ongoing local transmission, healthcare workers caring for patients with COVID-19, close contacts of infected persons, and travelers returning from locations where local spread has been reported.

The CDC has published a summary of evidence of comorbidities that are supported by meta-analysis/systematic review that have a significant association with risk of severe COVID-19 illness. These include the following conditions [14] :

Cancer

Cerebrovascular disease

Chronic kidney disease

COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease)

Diabetes mellitus, type 1 and type 2

Heart conditions (eg, heart failure, coronary artery disease, cardiomyopathies)

Immunocompromised state from solid organ transplant

Obesity (BMI 30 kg/m 2 or greater)

Pregnancy

Smoking, current or former

Comorbidities that are supported by mostly observational (eg, cohort, case-control, or cross-sectional) studies include the following [14] :

Children with certain underlying conditions

Down syndrome

HIV (human immunodeficiency virus)

Neurologic conditions, including dementia

Overweight (BMI 25 to less than 30 kg/m 2)

Other lung disease (including interstitial lung disease, pulmonary fibrosis, pulmonary hypertension)

Sickle cell disease

Solid organ or blood stem cell transplantation

Substance use disorders

Use of corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive medications

Comorbidities that are supported by mostly case series, case reports, or, if other study design or the sample size is small include the following [14] :

Cystic fibrosis

Thalassemia

Comorbidities supported by mixed evidence include the following [14] :

Asthma

Hypertension

Immune deficiencies

Liver disease

Such individuals should consider the following precautions [14] :

Stock up on supplies.

Avoid close contact with sick people.

Wash hands often.

Stay home as much as possible in locations where COVID-19 is spreading.

Develop a plan in case of illness.

Signs and symptoms

In a study that included 172 patients diagnosed with COVID-19 in January 2022, the estimated median incubation period was 2.8 days (SD, 1.20) among those infected with the Omicron variant (primarily sublineage BA.1). Most infections fell between 1 and 6 days. The distribution was significantly longer in patients with the Alpha variant (4.5 days), and the researchers’ previous study that used contact tracing data estimated a median incubation period of 3.7 days for the Delta variant. [15]

The following symptoms may indicate COVID-19 [16] :

Fever or chills (43-45%)

Cough (63-83%)

Shortness of breath or difficulty breathing (45.6%) [17]

Fatigue (63%)

Muscle or body aches (36-63%)

Headache (34-70%)

New loss of taste (54.2%) or smell (70.2%)

Sore throat (52.9%)

Congestion (67.8%) or runny nose (60.1%)

Nausea or vomiting (31.6%) [18]

Diarrhea (17.8%) [18]

Other reported symptoms have included the following:

Sputum production

Malaise

Respiratory distress

Neurologic (eg, headache, altered mentality)

The most common serious manifestation of COVID-19 appears to be pneumonia.

A complete or partial loss of the sense of smell (anosmia) has been reported as a potential history finding in patients eventually diagnosed with COVID-19 [19] ; however, rates of smell or taste dysruption have decreased as the pandemic has progressed. A study of 616,318 patients with COVID-19 found that 3431 had an associated disturbance in smell or taste; of those, the odds ratios were 0.50 among those infected with the Alpha variant; 0.44 among those infected with Delta; and 0.17 among those infected with Omicron (December 27, 2021–February 7, 2022). [20]

Diagnosis

COVID-19 should be considered a possibility (1) in patients with respiratory tract symptoms and newly onset fever or (2) in patients with severe lower respiratory tract symptoms with no clear cause. Suspicion is increased if such patients have been in an area with community transmission of SARS-CoV-2 or have been in close contact with an individual with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 in the preceding 14 days.

Microbiologic (PCR or antigen) testing is required for definitive diagnosis.

Patients who do not require emergency care are encouraged to contact their healthcare provider by phone. Patients with suspected COVID-19 who present to a healthcare facility should trigger infection-control measures. These patients should be evaluated in a private room with the door closed (an airborne infection isolation room is ideal) and instructed to wear a surgical mask. All other standard contact and airborne precautions should be observed, and treating healthcare personnel should wear eye protection. [21]

Management

Utilization of programs established by the FDA to allow clinicians access to investigational therapies during the pandemic has been essential. The expanded access (EA) and emergency use authorization (EUA) programs allowed for rapid deployment of potential therapies for investigation and investigational therapies with emerging evidence. A review by Rizk et al describes the role for each of these measures and their importance to providing medical countermeasures in the event of infectious disease and other threats. [22]

Remdesivir, an antiviral agent, was the first drug to gain full FDA approval for treatment of hospitalized adults and adolescents with COVID-19 disease in October 2020. [23] Since then, it has gained approval for adults and pediatric patients (aged 28 days and older who weigh at least 3 kg) with positive results of direct SARS-CoV-2 viral testing, who are hospitalized, or not hospitalized and have mild-to-moderate COVID-19, and are at high risk for progression to severe COVID-19, including hospitalization or death. [24]

The first vaccine to gain full FDA approval was mRNA-COVID-19 vaccine (Comirnaty; Pfizer) in August 2021. A second mRNA vaccine (Spikevax; Moderna) was approved by the FDA in January 2022. Additionally, each of these vaccines have EUAs for children as young as 6 months.EUAs have been issued for other vaccines.

Baricitinib (Olumiant), a Janus kinase inhibitor, gained FDA approval for hospitalized adults with COVID-19 disease who require supplemental oxygen, noninvasive or invasive mechanical ventilation, or ECMO. An EUA for children has been issued for baricitinib.

Similar to baricitinib, tocilizumab (Actemra), an interleukin 6 inhibitor, was approved by the FDA for hospitalized adults. An EUA remains in place for children aged 2 years and older.

EUAs have also been issued for other antivirals, vaccines and convalescent plasma in the United States. A full list of EUAs and access to the Fact Sheets for Healthcare Providers is available from the FDA.

Use of corticosteroids improves survival in hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19 disease requiring supplemental oxygen, with the greatest benefit shown in those requiring mechanical ventilation. [25]

Infected patients should receive supportive care to help alleviate symptoms. Vital organ function should be supported in severe cases. [26]

Numerous collaborative efforts to discover and evaluate effectiveness of antivirals, immunotherapies, monoclonal antibodies, and vaccines have rapidly emerged. Guidelines and reviews of pharmacotherapy for COVID-19 have been published. [26, 27, 28, 29, 30]

Background

Coronaviruses comprise a vast family of viruses, seven of which are known to cause disease in humans. Some coronaviruses that typically infect animals have evolved to infect humans. SARS-CoV-2 is likely one such virus, postulated to have originated in a large animal and seafood market.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) also are caused by coronaviruses that “jumped” from animals to humans. More than 8000 individuals developed SARS, nearly 800 of whom died of the illness (mortality rate, approximately 10%), before it was controlled in 2003. [31] MERS continues to resurface in sporadic cases. In late February 2022, a total of 2585 laboratory-confirmed cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) were reported worldwide (890 associated deaths; case-fatality ratio, 34.4%). [32]

Route of Transmission

The principal mode by which people are infected with SARS-CoV-2 is through exposure to respiratory droplets carrying infectious virus (generally within a space of 6 feet). Additional methods include contact transmission (eg, shaking hands) and airborne transmission [33] of droplets that linger in the air over long distances (usually greater than 6 feet). [34, 35, 36] Virus released in respiratory secretions (eg, during coughing, sneezing, talking) can infect other individuals via contact with mucous membranes.

On July 9, 2020, the WHO issued an update stating that airborne transmission may play a role in the spread of COVID-19, particularly involving “super spreader” events in confined spaces such as bars, although they stressed a lack of such evidence in medical settings. Thus, they emphasized the importance of social distancing and masks in prevention. [37] The WHO continues to support airborne transmission as a method of the disease's spread. [38]

The virus can also persist on surfaces to varying durations and degrees of infectivity, although this is not believed to be the main route of transmission. [35] One study found that SARS-CoV-2 remained detectable for up to 72 hours on some surfaces despite decreasing infectivity over time. Notably, the study reported that no viable SARS-CoV-2 was measured after 4 hours on copper or after 24 hours on cardboard. [39]

In a separate study, Chin and colleagues found the virus was very susceptible to high heat (70°C). At room temperature and moderate (65%) humidity, no infectious virus could be recovered from printing and tissue papers after a 3-hour incubation period or from wood and cloth by day 2. On treated smooth surfaces, infectious virus became undetectable from glass by day 4 and from stainless steel and plastic by day 7. “Strikingly, a detectable level of infectious virus could still be present on the outer layer of a surgical mask on day 7 (~0.1% of the original inoculum),” the researchers write. [40] Contact with fomites is thought to be less significant than person-to-person spread as a means of transmission. [35]

Viral shedding

The duration of viral shedding varies significantly and may depend on severity. A 2022 sytematic review and meta-analysis of 20 studies (866 participants) found that after symptom onset, the mean duration of RT-PCR positivity was 27.9 days, whereas the mean duration of isolation of replicant competent virus was 7.3 days. The mean duration of SARS-CoV-2 shedding was 26.5 days among immunocompetent individuals and 36.3 days among immunocompromised individuals. The mean duration of infectivity was 6.3 days among immunocompetent participants and 29.5 days among immunocompromised participants. The longest duration of infectivity was 18 days after symptom onset among immunocompetent patients compared with a maximum of 112 days among immunocompromised patients. [41]

Among 137 survivors of COVID-19, viral shedding based on testing of oropharyngeal samples ranged from 8 to 37 days, with a median of 20 days. [42] A different study found that repeated viral RNA tests using nasopharyngeal swabs were negative in 90% of cases among 21 patients with mild illness, whereas results were positive for longer durations in patients with severe COVID-19. [43] In an evaluation of patients recovering from severe COVID-19, Zhou and colleagues found a median shedding duration of 31 days (range, 18-48 days). [44] These studies have all used PCR detection as a proxy for viral shedding. The Korean CDC, investigating a cohort of patients who had prolonged PCR positivity, determined that infectious virus was not present. [45] These findings were incorporated into the CDC guidance on the duration of isolation following COVID-19 infection.

Additionally, patients with profound immunosuppression (eg, following hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation, receiving cellular therapies) may shed viable SARS-CoV-2 for at least 2 months. [46, 47]

SARS-CoV-2 has been found in the semen of men with acute infection, as well as in some male patients who have recovered. [48]

Asymptomatic/presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection and its role in transmission

Oran and Topol published a narrative review of multiple studies on asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Such studies and news articles reported rates of asymptomatic infection in several worldwide cohorts, including resident populations from Iceland and Italy, passengers and crew aboard the cruise ship Diamond Princess, homeless persons in Boston and Los Angeles, obstetric patients in New York City, and crew aboard the USS Theodore Roosevelt and Charles de Gaulle aircraft carriers, among several others. Almost half (40-45%) of SARS-CoV-2 infections were asymptomatic. [49]

Johansson et al from the CDC assessed transmission from presymptomatic, never symptomatic, and symptomatic individuals across various scenarios to determine the infectious period of transmitting SARS-CoV-2. Results from their base case determined 59% of all transmission came from asymptomatic transmission, 35% from presymptomatic individuals and 24% from individuals who never developed symptoms. They estimate at least 50% of new infections came from exposure to individuals with infection, but without symptoms. [50]

Zou and colleagues followed viral expression through infection via nasal and throat swabs in a small cohort of patients. They found increases in viral loads at the time that the patients became symptomatic. One patient never developed symptoms but was shedding virus beginning at day 7 after presumed infection. [51]

Epidemiology

Coronavirus outbreak and pandemic

As of April 5, 2023, confirmed COVID-19 infections numbered over 762 million individuals worldwide and have resulted in nearly 7 million deaths. [52] Additionally, the World Health Organization estimates the full death toll associated directly or indirectly with the pandemic is approximately 15 million.

In the United States, over 104 million reported cases of COVID-19 have been confirmed as of March 29, 2023, resulting in more than 1,125,000 deaths. [53] The pandemic caused approximately 375,000 deaths in the United States during 2020. The age-adjusted death rate increased by 15.9% in 2020, making it the third leading cause of death after heart disease and cancer. [54] During 2021, COVID-19 was associated with 416,893 deaths in the United States, and was again the third leading cause of death. Approximately 75% of deaths in the United States from COVID-19 occurred in individuals aged 65 years and older. [55]

Racial health disparities

Communities of color have been disproportionally devastated by COVID-19 in the United States and in Europe. Data from New Orleans illustrated these disparities. African Americans represent 31% of the population but 76.9% of the hospitalizations and 70.8% of the deaths. [56]

A systematic review of 52 studies found racial and ethnic minority groups were at higher risk for COVID-19 infection and hospitalization, confirmed diagnosis, and death. Most of the studies listed factors such as low education level, poverty, poor housing conditions and overcrowded households, low household income, and not speaking the national language in a country as risk factors for COVID-19 incidence/infection, death, and confirmed diagnosis. [57]

Data suggest the cumulative effects of health disparities are the driving force. The prevalence of chronic (high-risk) medical conditions is higher, and access to healthcare may be less available. Finally, socioeconomic status may decrease the ability to isolate and avoid infection. [58, 59]

A prospective cohort study surveyed 170 adult patients who had recovered from COVID-19 1 year prior, during March and April of 2020. The patients participated in a telephone survey during March and April of 2021.

Almost half (79 patients; 46.5%) were of Hispanic ethnicity and 27.1% (46 patients) were African American. Job loss after COVID-19 diagnosis was highest among Hispanics (31/79; 39.2%) and African Americans (16/46; 34.7%). Hispanic individuals (31/79; 39.2%) and African Americans (17/46; 36.9%) also reported the most financial distress after COVID-19 diagnosis.

Compared with Whites, Hispanics were more likely to experience job loss (odds ratio [OR], 4.456), as were African Americans (OR, 4.465). [60]

Hobbs et al compared MIS-C cases (38 cases) and COVID-19 hospitalizations (74 children) among non-Hispanic Black and White children in a defined catchment 16-county area of Mississippi.

Compared with White children, Black children had an almost fivefold cumulative incidence of MIS-C (40.7 vs 8.3 cases per 100,000 SARS-CoV-2 infections). The cumulative incidence of hospitalization for COVID-19 was almost twice as high in Black children compared with White children (62.3 among Black vs 33.1 among White children per 100,000 SARS-CoV-2 infections). [61]

Ward et al conducted a retrospective analysis of COVID-19 cases reported to the Alaska Department of Health and Social Services from March 12, 2020-December 31, 2021. The age-adjusted COVID-19 incidence among American Indian (AI)/Alaska Native (AN) individuals (26,583 per 100,000 standard population) was approximately twice the rate among White individuals (11,935).

The age-adjusted COVID-19-associated hospitalization rate (273; rate ratio [RR], 2.72) and the age-adjusted COVID-19 related mortality rate (104; RR, 2.86) among AI/AN individuals were nearly three times those of White study participants. [62]

The overall age-adjusted death rate increased by 15.9% in 2020. Death rates were highest among non-Hispanic Black persons and non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native persons. [54]

CDC maintains a COVID-19 Data Tracker for near real time updates.

Young Adults

Outcomes from COVID-19 disease in young adults have been described by Cunningham and colleagues. Of 3200 adults aged 18 to 34 years hospitalized in the United States with COVID-19, 21% were admitted to the ICU, 10% required mechanical ventilation, and 3% died. Comorbidities included obesity (33%; 25% overall were morbidly obese), diabetes (18%), and hypertension (16%). Independent predictors of death or mechanical ventilation included hypertension, male sex, and morbid obesity. Young adults with multiple risk factors for poor outcomes from COVID-19 compared similarly to middle-aged adults without such risk factors. [63]

A study from South Korea found that older children and adolescents are more likely to transmit SARS CoV-19 to family members than are younger children. The researchers reported that the highest infection rate (18.6%) was in household contacts of patients with COVID-19 aged 10 to 19 years, and the lowest rate (5.3%) was in household contacts of those aged 0 to 9 years. [64] Teenagers have been the source of clusters of cases, illustrating the role of older children. [65]

COVID-19 in children

Data continue to emerge regarding the incidence and effects of COVID-19, especially for severe disease. [66] A severe multisystem inflammatory syndrome linked to COVID-19 infection has been described in children. [67, 68, 69, 70, 66]

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) reports children represent 18.3% of all COVID-19 cases in the 49 states reporting by age; nearly 15 million children have tested positive in the United States since the onset of the pandemic as of October 27, 2022. This represents an overall rate of 19,787 cases per 100,000 children. During the 2-week period of October13-27, 2022, there was less than a 1% increase in the cumulated number of children who tested positive, representing 47,261 new confirmed cases. In the week from October 20-27, 2022, cases in children numbered 14,868 and represented 11.1% of the new weekly cases. [71]

AAP has issued interim guidance for follow-up care of children following a SARS-CoV-2 infection.

In the United States, a modeling study found one child loses a parent or caregiver for every four COVID-19 associated deaths. From April 1, 2020 through June 30, 2021, more than 140,000 children younger than 18 years in the United States lost a parent, custodial grandparent, or grandparent caregiver who provided the child’s home and basic needs, including love, security, and daily care. Overall, approximately one of 500 US children has experienced COVID-19-associated orphanhood or the death of a grandparent caregiver. Racial, ethnic, and geographic disparities in COVID-19-associated death of caregivers were also seen – children of racial and ethnic minorities accounted for 65% of those who lost a primary caregiver due to the pandemic. [72]

As of late June 2022, approximately 85,825,048 cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection and 1,007,964 associated deaths have been reported in the United States. [73] Persons younger than 21 years constitute 26% of the US population. [74]

Clinical characteristics and outcomes of hospitalized children and adolescents aged 1 month to 21 years with COVID-19 in the New York City area have been described. These observations alerted clinicians to rare, but severe illness in children. Of 67 children who tested positive for COVID-19, 21 (31.3%) were managed as outpatients. Among 46 hospitalized patients, 33 (72%) were admitted to the general pediatric medical unit and 13 (28%) to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU). Obesity and asthma were highly prevalent, but not significantly associated with PICU admission (P = .99).

Admission to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) was significantly associated with higher C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, and pro-B type natriuretic peptide levels and platelet counts (P < .05 for all). Patients in the PICU were more likely to require high-flow nasal cannula (P = .0001) and were more likely to have received remdesivir through compassionate release (P < .05). Severe sepsis and septic shock syndromes were observed in 7 (53.8%) patients in the PICU. ARDS was observed in 10 (77%) PICU patients, 6 (46.2%) of whom required invasive mechanical ventilation for a median of 9 days. Of the 13 patients in the PICU, 8 (61.5%) were discharged home, and 4 (30.7%) patients remained hospitalized on ventilatory support at Day 14. One patient died after withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy associated with metastatic cancer. [75]

A case series of 91 children who tested positive for COVID-19 in South Korea showed 22% were asymptomatic during the entire observation period. Among 71 symptomatic cases, 47 children (66%) had unrecognized symptoms before diagnosis, 18 (25%) developed symptoms after diagnosis, and 6 (9%) were diagnosed at the time of symptom onset. Twenty-two children (24%) had lower respiratory tract infections. The mean (SD) duration of the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in upper respiratory samples was 17.6 (6.7) days. These results lend more data to unapparent infections in children that may be associated with silent COVID-19 community transmission. [76]

An Expert Consensus Statement has been published that discusses diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of COVID-19 in children.

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children

Media reports and a health alert from the New York State Department of Health drew initial attention to a newly recognized multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) associated with COVID-19. Since then, MIS-C cases have been reported across the United States and Europe, and the American Academy of Pediatrics has published interim guidance.

Symptoms are reminiscent of Kawasaki disease, atypical Kawasaki disease, or toxic shock syndrome. All patients had persistent fevers, and more than half had rashes and abdominal complaints. Interestingly, respiratory symptoms were rarely described. Many patients did not have PCR results positive for COVID-19, but many had strong epidemiologic links with close contacts who tested positive. Furthermore, many had antibody tests positive for SARS-CoV-2. These findings suggest recent past infection, and this syndrome may be a postinfectious inflammatory syndrome. The CDC case definition requires:

An individual younger than 21 years presenting with fever ≥38.0°C for ≥24 hours, laboratory evidence of inflammation (including an elevated C-reactive protein [CRP], erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR], fibrinogen, procalcitonin, D-dimer, ferritin, lactic acid dehydrogenase [LDH], or interleukin 6 [IL-6], elevated neutrophils, reduced lymphocytes, and low albumin), and evidence of clinically severe illness requiring hospitalization, with multisystem (≥2) organ involvement (cardiac, renal, respiratory, hematologic, gastrointestinal, dermatologic, or neurological); AND

No alternative plausible diagnoses; AND

Positive for current or recent SARS-CoV-2 infection by RT-PCR, serology, or antigen test; or exposure to a suspected or confirmed COVID-19 case within the 4 weeks prior to the onset of symptoms.

Jiang and colleagues reviewed the literature on MIS-C noting the multiple organ system involvement. Unlike classic Kawasaki Disease, the children tended to be older and those of Asian ethnicity tended to be spared. [77]

A case series compared 539 patients who had MIS-C with 577 children and adolescents who had severe COVID-19. The patients with MIS-C were typically younger (predominantly aged 6-12 years) and more likely to be non-Hispanic Black. They were less likely to have an underlying chronic medical condition, such as obesity. Severe cardiovascular or mucocutaneous involvement was more common in those with MIS-C. Patients with MIS-C also had higher neutrophil to lymphocyte ratios, higher CRP levels, and lower platelet counts than those with severe COVID-19. [78]

COVID-19 in pregnant individuals and neonates

Pregnant women are at increased risk for severe COVID-19–related illness, and COVID-19 is associated with an increased risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes including intrauterine growth restriction, premature rupture of membranes and preterm delivery, fetal distress, spontaneous abortion, and stillbirth, and maternal and neonatal complications. [79, 80, 81]

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported in November 2021 that maternal COVID-19 infection increases risk for stillbirth compared with women without COVID-19. From March 2020 to September 2021, 8154 stillbirths were reported, affecting 0.65% of births by women without COVID and 1.26% of births by women with COVID, for a relative risk (RR) of 1.90. The magnitude of association was higher during the period of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant predominance than during the pre-Delta period. [82]

A multicenter study involving 16 Spanish hospitals reported outcomes of 242 pregnant patients diagnosed with COVID-19 during the third trimester from March 13 to May 31, 2020. They and their 248 newborns were monitored until the infant was 1 month old. Pregnant patients with COVID-19 who were hospitalized had a higher risk for cesarean birth (P = 0.027). Newborns whose mothers were hospitalized for COVID-19 infection had a higher risk for premature delivery (P = 0.006). No infants died and no vertical or horizontal transmission was detected. Exclusive breastfeeding was reported for 41.7% of infants at discharge and 40.4% at 1 month. [83]

A cohort study of pregnant patients (n = 64) with severe or critical COVID-19 disease hospitalized at 12 US institutions between March 5, 2020, and April 20, 2020 has been published. At the time of the study, most (81%) received hydroxychloroquine; 7% of those with severe disease and 65% with critical disease received remdesivir. All of those with critical disease received either prophylactic or therapeutic anticoagulation. One case of maternal cardiac arrest occurred, but there were no cases of cardiomyopathy or death. Half (n = 32) delivered during their hospitalization (34% severe group; 85% critical group). Additionally, 88% with critical disease delivered preterm during their disease course, with 16 of 17 (94%) pregnant women giving birth through cesarean delivery. Overall, 15 of 20 (75%) with critical disease delivered preterm. There were no stillbirths or neonatal deaths or cases of vertical transmission. [84]

Adhikari and colleagues published a cohort study evaluating 252 pregnant patients with COVID-19 in Texas. Maternal illness at initial presentation was asymptomatic or mild in 95% of them, and 3% developed severe or critical illness. Compared with COVID negative pregnancies, there was no difference in the composite primary outcome of preterm birth, preeclampsia with severe features, or cesarean delivery for abnormal fetal heart rate. Early neonatal SARS-CoV-2 infection occurred in six of 188 tested infants,(3%) primarily born to asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic mothers. There were no placental pathologic differences by illness severity. [85]

Breastfeeding

A study by Chambers and colleagues found human milk is unlikely to transmit SARS-CoV-2 from infected mothers to infants. The study included 64 milk samples provided by 18 mothers infected with COVID-19. Samples were collected before and after COVID-19 diagnosis. No replication-competent virus was detectable in any of their milk samples compared with samples of human milk that were experimentally infected with SARS-CoV-2. [86]

Mothers or birthing parents who have been infected with SARS CoV-2 may have neutralizing antibodies expressed in their milk. In an evaluation of 1-7 milk samples over 2 months from 64 women, 75% contained SARS-CoV-2-specific IgA and 7% persited for at least 2 months. These results support recommendations to continue breastfeeding/chestfeeding with masking during mild-to-moderate maternal COVID-19 illness. [87]

COVID-19 in patients with HIV

Data for people with HIV and coronavirus are emerging. A multicenter registry has published outcomes for 286 patients with HIV who tested positive for COVID-19 between April 1 and July 1, 2020. Patient characteristics included mean age of 51.4 years, 25.9% were female, and 75.4% were African-American or Hispanic. Most patients (94.3%) were on antiretroviral therapy, 88.7% had HIV virologic suppression, and 80.8% had comorbidities. Within 30 days of positive SARS-CoV-2 testing, 164 (57.3%) patients were hospitalized, and 47 (16.5%) required ICU admission. Mortality rates were 9.4% (27/286) overall, 16.5% (27/164) among those hospitalized, and 51.5% (24/47) among those admitted to an ICU. [88]

Multiple case series have subsequently been published. Most suggest similar outcomes in patients living with HIV as the general patient population. [89, 90] Severe COVID-19 has been seen, however, suggesting that neither antiretroviral therapy of HIV infection are protective. [88, 91]

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 43 studies including 692,032 COVID-19 cases found that 9097 (1.3%) were among people living with HIV (PLWH); the global prevalence of PLWH among cases of COVID-19 was 2%, and the highest prevalence occurred in sub-Saharan Africa. The relative risk (RR) for severe COVID-19 in PLWH was significant only in Africa, at 1.14, whereas the RR for mortality was 1.5 worldwide, suggesting that HIV infection may be associated with increased death from COVID-19. [92]

COVID-19 in clinicians

Among a sample of healthcare providers who routinely cared for patients with COVID-19 in 13 US academic medical centers from February 1, 2020, 6% had evidence of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection, with considerable variation by location that generally correlated with community cumulative incidence. Among participants who had positive test results for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, approximately one third did not recall any symptoms consistent with an acute viral illness in the preceding months, nearly one half did not suspect that they previously had COVID-19, and approximately two thirds did not have a previous positive test result demonstrating an acute SARS-CoV-2 infection. [93]

Prognosis

During January to December 2020, the estimated 2020 age-adjusted death rate increased for the first time since 2017, with an increase of 15.9% compared with 2019, from 715.2 to 828.7 deaths per 100,000 population. COVID-19 was the underlying or a contributing cause of 377,883 deaths (91.5 deaths per 100,000). COVID-19 death rates were highest among males, older adults, non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native (AI/AN) persons, and Hispanic persons. Age-adjusted death rates was highest among Black (1105.3) and AI/AN persons (1024). [54]

Mortality and diabetes

Type 1 and type 2 diabetes are both independently associated with a significant increased odds of in-hospital death with COVID-19. In a nationwide analysis in England of 61,414,470 individuals in the registry alive as of February 19, 2020, 0.4% had a recorded diagnosis of type 1 diabetes and 4.7% of type 2 diabetes. A total of 23,804 COVID-19 deaths in England were reported as of May 11, 2020; one third were in people with diabetes, including 31.4% with type 2 diabetes and 1.5% with type 1 diabetes. Upon multivariate adjustment, the odds of in-hospital COVID-19 death were 3.5 for those with type 1 diabetes and 2.03 for those with type 2 diabetes, compared with deaths among individuals without known diabetes. Further adjustment for cardiovascular comorbidities found the odds ratios were still significantly elevated in both type 1 (2.86) and type 2 (1.81) diabetes. [94]

The CDC estimates diabetes is associated with a 20% increased odds of in-hospital mortality. [54]

Hospitalization and cardiometabolic conditions

O’Hearn et al estimate nearly 2 in 3 adults hospitalized for COVID-19 in the United States have associated cardiometabolic conditions including total obesity (BMI 30 kg/m2 or greater), diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and heart failure. [95]

Virology

The full genome of SARS-CoV-2 was first posted by Chinese health authorities soon after the initial detection, facilitating viral characterization and diagnosis. The CDC analyzed the genome from the first US patient who developed the infection on January 24, 2020, concluding that the sequence is nearly identical to the sequences reported by China. [1] SARS-CoV-2 is a group 2b beta-coronavirus that has at least 70% similarity in genetic sequence to SARS-CoV. [96] Like MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 originated in bats. [1] Viral variants emerge when the virus develops one or more mutations that differentiate it from the predominant virus variants circulating in a population. The CDC surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 variants includes US COVID-19 cases caused by variants. The site also includes which mutations are associated with particular variants. The CDC has launched a genomic surveillance dashboard and a website tracking US COVID-19 case trends caused by variants. Researchers are studying how variants may or may not alter the extent of protection by available vaccines. For more information, see the Medscape topic COVID-19 Variants. Omicron The Omicron variant (B.1.1.529), initially identified in South Africa, was declared a variant of concern in the United States by the CDC November 30, 2021. This VOC contains several dozen mutations, including a large number in the spike gene, more than previous VOCs. These mutations include several associated with increased transmission. The Omicron variant quickly became dominant in the United States. As of January 8, 2022, it accounted for over 98% of circulating virus, compared with less than 8% on December 11, 2021. Antiviral agent effectiveness An in vitro study published in December 2021 indicate that remdesivir, nirmatrelvir, molnupiravir, EIDD-1931, and GS-441524 (oral prodrug of remdesivir) retain their activity against the VOCs Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, and Omicron. [97] Vaccine effectiveness A preprinted, nonpeer reviewed article of routine surveillance data from South Africa suggests the Omicron variant may evade immunity from prior infection. Among 2,796,982 individuals with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 who had a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2 at least 90 days before November 27, 2021, there were 35,670 suspected reinfections identified. [98] In another preprinted article, neutralization performed with sera from double or triple BNT162b2-vaccinated individuals (6, 0.5 or 3 months after last vaccination/booster) revealed an 11.4-, 37.0- and 24.5-fold reduction, respectively. Sera from double mRNA-1273-vaccinated and additionally BNT162b2-vaccinated individuals (sampled 6 or 0.5 months after last vaccination/booster) showed a 20- and 22.7-fold reduction in the neutralization capacity. [99] Delta The Delta variant (B.1.617.2) that was first identified in India became the dominant variant in the United States in mid-July 2021. This variant increases ACE binding and transmissibility. An approximate 6.8-fold decreased neutralization for mRNA vaccines and convalescent plasma was observed with the Delta variant. [100, 101] However, a study completed by Public Health England found the BNT162b2 vaccine was only slightly reduced from 93.7% with the B.1.1.7 variant to 88% for the Delta variant 2 weeks after the second dose. [102] As the Omicron variant transmission increased rapidly in December 2021, the Delta variant now accounts for less than 2% of cases in the United States. Alpha The CDC tracks variant proportions circulating in the United States and estimates the B.1.1.7 variant (Alpha) that was first detected in the United Kingdom accounted for over 44% of cases from January 2 to March 27, 2021. On April 7, 2021, the CDC announced B.1.1.7 was the dominant strain circulating in the United States. It was the dominant strain until mid-July 2021, when the Delta variant became the dominant strain. At the same time that the transmission of the wild type virus was dropping, the variant increased, suggesting that the same recommendations (eg, masks, social distancing) may not be enough. The UK variant is also infecting more children (aged 19 years and younger) than the wild type, indicating that it may be more transmissible in children. This has raised concerns because a relative sparing of children has been observed to date. This variant is hypothesized to have a stronger ACE binding than the original variant, which was felt to have trouble infecting younger individuals as they express ACE to a lesser degree. [103] Beta The E484K mutation was found initially in the South Africa VOC (B.1.351 [Beta]) and also with the Brazil variants in late 2020, and was observed in the UK variant in early February 2021. Position 484 and 501 mutations that are both present in the South African variant, and the combination is a concern that immune escape may occur. These mutations, among others, have combined to create the VOC B.1.351. [104] Gamma The Brazil VOC P.1 (Gamma) was responsible for an enormous second surge of infections. Sabino et al describe resurgence of COVID-19 in Manaus, Brazil in January 2021, despite a high seroprevalence. A study of blood donors indicated that 76% of the population had been infected with SARS-CoV-2 by October 2020. Hospitalizations for COVID-19 in Manaus numbered 3431 in January 1 to 19, 2021 compared with 552 for December 1 to 19, 2020. Hospitalizations had remained stable and low for 7 months prior to December 2020. Several postulated variables regarding this resurgence include waning titers to the original viral lineage and the high prevalence of the P.1 variant, which was first discovered in Manaus. [105] In addition, researchers are monitoring emergence of a second variant in Brazil, P.2, identified in Rio de Janeiro. As of September 21, 2021, the CDC lists P.2 as a variant being monitored. Epsilon VOCs B.1.427 (Epsilon) and B.1.429 (Epsilon) emerged in California. These variants accounted for 2.9% and 6.9% of variants circulating in the United States between January 2 to March 27, 2021. An approximate 20% increase in transmission has been observed with this variant.

Clinical Presentation

History

Presentations of COVID-19 range from asymptomatic/mild symptoms to severe illness and mortality. Common symptoms include fever, cough, and shortness of breath. [106] Other symptoms, such as malaise and respiratory distress, also have been described. [96]

Symptoms may develop 2 days to 2 weeks after exposure to the virus. [106] A pooled analysis of 181 confirmed cases of COVID-19 outside Wuhan, China, found the mean incubation period was 5.1 days, and that 97.5% of individuals who developed symptoms did so within 11.5 days of infection. [107]

Symptom rebound and viral rebound have been described in patients (with or without antiviral treatment). In untreated patients, those (n = 563) receiving placebo in the ACTIV-2/A5401 (Adaptive Platform Treatment Trial for Outpatients with COIVD-19) platform trial recorded 13 symptoms daily between days 1 and 28. Symptom rebound was identified in 26% of participants at a median of 11 days after initial symptom onset. Viral rebound was detected in 31% and high-level viral rebound in 13% of participants. [108]

The following symptoms may indicate COVID-19 [106] :

Fever or chills

Cough

Shortness of breath or difficulty breathing

Fatigue

Muscle or body aches

Headache

New loss of taste or smell

Sore throat

Congestion or runny nose

Nausea or vomiting

Diarrhea

Other reported symptoms include the following:

Sputum production

Malaise

Respiratory distress

Neurologic (eg, headache, altered mentality)

Wu and McGoogan reported that, among 72,314 COVID-19 cases reported to the CCDC, 81% were mild (absent or mild pneumonia), 14% were severe (hypoxia, dyspnea, >50% lung involvement within 24-48 hours), 5% were critical (shock, respiratory failure, multiorgan dysfunction), and 2.3% were fatal. [109] These general symptom distributions have been reconfirmed across multiple observations. [110, 111]

Clinicians evaluating patients with fever and acute respiratory illness should obtain information regarding travel history or exposure to an individual who recently returned from a country or US state experiencing active local transmission. [112]

Williamson and colleagues, in an analysis of 17 million patients, reaffirmed that severe COVID-19 and mortality was more common in males, older individuals, individuals in poverty, Black persons, and patients with medical conditions such as diabetes and severe asthma, among others. [113]

A multicenter observational cohort study conducted in Europe found frailty was a greater predictor of mortality than age or comorbidities. [114]

Type A blood has been suggested as a potential factor that predisposes to severe COVID-19, specifically in terms of increasing the risk for respiratory failure. Blood type O appears to confer a protective effect. [115, 116]

Patients with suspected COVID-19 should be reported immediately to infection-control personnel at their healthcare facility and the local or state health department. CDC guidance calls for the patient to be cared for with airborne and contact precautions (including eye shield) in place. [21] Patient candidates for such reporting include those with fever and symptoms of lower respiratory illness who have travelled from Wuhan City, China, within the preceding 14 days or who have been in contact with an individual under investigation for COVID-19 or a patient with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 in the preceding 14 days. [112]

A complete or partial loss of the sense of smell (anosmia) has been reported as a potential history finding in patients eventually diagnosed with COVID-19. [19] A phone survey of outpatients with mildly symptomatic COVID-19 found that 64.4% (130 of 202) reported any altered sense of smell or taste. [117] In a European study of 72 patients with PCR results positive for COVID-19, 53 patients (74%) reported reduced olfaction, whereas 50 patients (69%) reported a reduced sense of taste. Forty-nine patients (68%) reported both symptoms. [118]

Physical Examination

Patients who are under investigation for COVID-19 should be evaluated in a private room with the door closed (an airborne infection isolation room is ideal) and asked to wear a surgical mask. All other standard contact and airborne precautions should be observed, and treating healthcare personnel should wear eye protection. [21]

The most common serious manifestation of COVID-19 upon initial presentation is pneumonia. Fever, cough, dyspnea, and abnormalities on chest imaging are common in these cases. [119, 120, 121, 122]

Huang and colleagues found that, among patients with pneumonia, 99% had fever, 70% reported fatigue, 59% had dry cough, 40% had anorexia, 35% experienced myalgias, 31% had dyspnea, and 27% had sputum production. [119]

Complications Complications of COVID-19 include pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, cardiac injury, arrhythmia, septic shock, liver dysfunction, acute kidney injury, and multi-organ failure, among others. Approximately 5% of patients with COVID-19, and 20% of those hospitalized, experience severe symptoms necessitating intensive care. The common complications among hospitalized patients include pneumonia (75%), ARDS (15%), AKI (9%), and acute liver injury (19%). Cardiac injury has been increasingly noted, including troponin elevation, acute heart failure, dysrhythmias, and myocarditis. Ten percent to 25 percent of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 experience prothrombotic coagulopathy resulting in venous and arterial thromboembolic events. Neurologic manifestations include impaired consciousness and stroke. ICU case fatality is reported up to 40%. [110] Long COVID As the COVID-19 pandemic has matured, more patients have reported long-term, post-infection sequelae. Most patients recover fully, but those who do not have reported adverse symptoms such as fatigue, dyspnea, cough, anxiety, depression, inability to focus (ie, “brain fog”), gastrointestinal problems, sleep difficulties, joint pain, and chest pain lasting weeks to months after the acute illness. Long-term studies are underway to understand the nature of these complaints. [123] Post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 (PASC) infection is the medical term for what is commonly called long COVID or "long haulers". The NIH includes discussion of persistent symptoms or organ dysfunction after acute COVID-19 within guidelines that discuss the clinical spectrum of the disease. [124] The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) issued guidelines on care of long COVID that define the syndrome as: signs and symptoms that develop during or after an infection consistent with COVID-19, continue for more than 12 weeks, and are not explained by an alternative diagnosis. [125] Please see Long COVID-19. Future public health implications Public health implications for long COVID need to be examined, as reviewed by Datta et al. As with other infections (eg, Lyme disease, syphilis, Ebola), late inflammatory and virologic sequelae may emerge. Accumulation of evidence beyond the acute infection and postacute hyperinflammatory illness is important to evaluate to gain a better understanding of the full spectrum of the disease. [126] Thrombotic manifestations of severe COVID-19 are caused by the ability of SARS-CoV-2 to invade endothelial cells via angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE-2), which is expressed on the surface of endothelial cells. Subsequent endothelial inflammation, complement activation, thrombin generation, platelet and leukocyte recruitment, and the initiation of innate and adaptive immune responses culminate in immunothrombosis, and can ultimately cause microthrombotic complications (eg, DVT, PE, stroke). [127] Kotecha et al describe patterns of myocardial injury in hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19 who had elevated troponin levels. During convalescence, myocarditis-like injury was observed, with limited extent and minimal functional consequence. However, in a proportion of patients, there was evidence of possible ongoing localized inflammation. Roughly 25% of patients had ischemic heart disease, of which two thirds had no previous history. [128] Reinfection COVID-19 reinfection is defined as an infected person who has undergone full vaccination, whether they have had a booster or boosters. According to the CDC, reinfection is COVID-19 infection of an individual with 2 different viral strains that occurs at least 45 days apart. It also may occur when an individual has 2 positive CoV-2 RT-PCR tests with negative tests between the 2 positive tests. [129] It is essential to determine reinfection rates to establish the effectiveness of current vaccine prophylaxis. Reinfection in vaccinated and non-vaccinated persons probably is due to a variant. [129, 130] It is important to differentiate reinfection from reactivation or relapse of the virus, which occurs in a clinically recovered person within the first 4 weeks of infection, during which viral RNA testing has remained positive. During relapse, a tiny viral load of dormant virus reactivates, the reason of which often is unclear. The only way to prove this state is to show that genetic samples taken at the beginning and at the time of reactivation differ genetically; such testing is unusual at the beginning of a person’s illness.

Workup

Approach Considerations

Diagnostic testing for SARS-CoV-2 infection can be conducted by the CDC, state public health laboratories, hospitals using their own developed and validated tests, and some commercial reference laboratories. [131]

State health departments with a patient under investigation (PUI) should contact CDC’s Emergency Operations Center (EOC) at 770-488-7100 for assistance with collection, storage, and shipment of clinical specimens for diagnostic testing. Specimens from the upper respiratory tract, lower respiratory tract, and serum should be collected to optimize the likelihood of detection. [112]

The FDA now recommends that nasal swabs that access just the front of the nose be used in symptomatic patients, allowing for (1) a more comfortable and simplified collection method and (2) self-collection at collection sites. [132]

Various organizations, including the CDC, have published guidelines on COVID-19.

Laboratory Studies

Signs and symptoms of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) may overlap with those of other respiratory infections; therefore, it is important to perform laboratory testing to specifically identify symptomatic individuals infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).

Three types of tests may be utilized to determine if an individual has been infected with SARS-CoV-2:

Viral nucleic acid (RNA) detection

Viral antigen detection

Detection of antibodies to the virus

Viral tests (nucleic acid or antigen detection tests) are used to assess acute infection, whereas antibody tests provide evidence of prior infection with SARS-CoV-2. Home sample collection kits for COVID-19 testing have been available by prescription; in December 2020, the LabCorp Pixel COVID-19 Test Home Collection Kit became the first to receive an FDA EUA for nonprescription use.

The FDA has advised against the use of antibody tests to ascertain immunity or protection from COVID-19, particularly in patients who have been vaccinated against the disease. According to the agency, differences between antibodies that arise from prior SARS-CoV-2 infection and those induced by vaccination leave the tests unable to determine whether an individual has achieved protection through a vaccine.

Laboratory findings in patients with COVID-19

Leukopenia, leukocytosis, and lymphopenia were common among early cases. [96, 119]

Lactate dehydrogenase and ferritin levels are commonly elevated. [119]

Wu and colleagues [133] reported that, among 200 patients with COVID-19 who were hospitalized, older age, neutrophilia, and elevated lactate dehydrogenase and D-dimer levels increased the risks for ARDS and death.

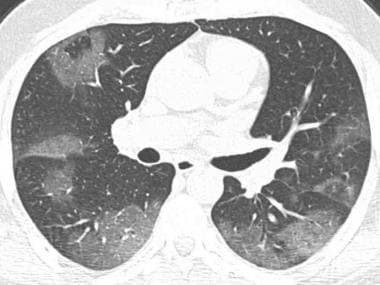

CT Scanning

Chest computed tomography (CT) scanning in patients with COVID-19–associated pneumonia usually shows ground-glass opacification, possibly with consolidation. Some studies have reported that abnormalities on chest CT scans are usually bilateral, involve the lower lobes, and have a peripheral distribution. Pleural effusion, pleural thickening, and lymphadenopathy have also been reported, although with less frequency. [119, 134, 135]

Bai and colleagues reported the following common chest CT scanning features among 201 patients with CT abnormalities and positive RT-PCR results for COVID-19 [136] :

Peripheral distribution (80%)

Ground-glass opacity (91%)

Fine reticular opacity (56%)

Vascular thickening (59%)

Less-common features on chest CT scanning included the following [136] :

Central and peripheral distribution (14%)

Pleural effusion (4.1%)

Lymphadenopathy (2.7%)

The American College of Radiology (ACR) recommends against using CT scanning for screening or diagnosis but instead reserving it for management in hospitalized patients. [137]

At least two studies have reported on manifestations of infection in apparently asymptomatic individuals. Hu and colleagues reported on 24 asymptomatic infected persons in whom chest CT scanning revealed ground-glass opacities/patchy shadowing in 50% of cases. [138] Wang and colleagues reported on 55 patients with asymptomatic infection, two thirds of whom had evidence of pneumonia as revealed by CT scanning. [139]

Progression of CT abnormalities

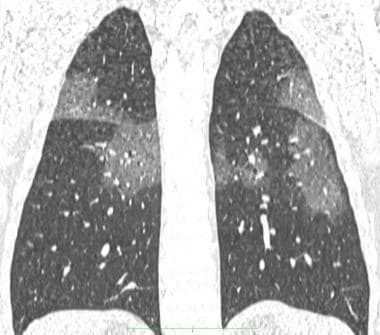

Li and colleagues recommend high-resolution CT scanning and reported the following CT changes over time in patients with COVID-19 among three Chinese hospitals:

Early phase: Multiple small patchy shadows and interstitial changes begin to emerge in a distribution beginning near the pleura or bronchi rather than the pulmonary parenchyma.

Progressive phase: The lesions enlarge and increase, evolving to multiple ground-glass opacities and infiltrating consolidation in both lungs.

Severe phase: Massive pulmonary consolidations occur, while pleural effusion is rare.

Dissipative phase: Ground-glass opacities and pulmonary consolidations are absorbed completely. The lesions begin evolving into fibrosis. [140]

Axial chest CT demonstrates patchy ground-glass opacities with peripheral distribution.

Coronal reconstruction chest CT of the same patient above, showing patchy ground-glass opacities.

Axial chest CT shows bilateral patchy consolidations (arrows), some with peripheral ground-glass opacity. Findings are in peripheral and subpleural distribution.

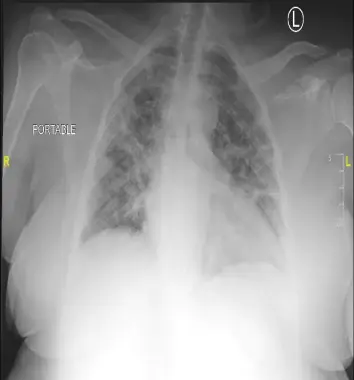

Chest Radiography

In a retrospective study of patients in Hong Kong with COVID-19, common abnormalities on chest radiography, when present, included consolidation (30 of 64 patients; 47%) and ground-glass opacities (33%). Consolidation was commonly bilateral and of lower zone distribution. Pleural effusion was an uncommon finding. Severity on chest radiography peaked 10 to 12 days after symptom onset. [141]

Chest radiography may reveal pulmonary infiltrates. [142]

The heart is normal in size. There are diffuse, patchy opacities throughout both lungs, which may represent multifocal viral/bacterial pneumonia versus pulmonary edema. These opacities are particularly confluent along the periphery of the right lung. There is left midlung platelike atelectasis. Obscuration of the left costophrenic angle may represent consolidation versus a pleural effusion with atelectasis. There is no pneumothorax.

The heart is normal in size. There are bilateral hazy opacities, with lower lobe predominance. These findings are consistent with multifocal/viral pneumonia. No pleural effusion or pneumothorax are seen.

The heart is normal in size. Patchy opacities are seen throughout the lung fields. Patchy areas of consolidation at the right lung base partially silhouettes the right diaphragm. There is no effusion or pneumothorax. Degenerative changes of the thoracic spine are noted.

The same patient as above 10 days later.

The trachea is in midline. The cardiomediastinal silhouette is normal in size. There are diffuse hazy reticulonodular opacities in both lungs. Differential diagnoses include viral pneumonia, multifocal bacterial pneumonia or ARDS. There is no pleural effusion or pneumothorax.

Treatment & Management

Approach Considerations

Utilization of programs established by the FDA to allow clinicians to gain access to investigational therapies during the pandemic has been essential. The expanded access (EA) and emergency use authorization (EUA) programs allowed for rapid deployment of potential therapies for investigation and investigational therapies with emerging evidence. A review by Rizk et al describes the role for each of these measures, and their importance to providing medical countermeasures in the event of infectious disease and other threats. [22]

Remdesivir, an antiviral agent, was the first drug to gain full FDA approval for treatment of hospitalized adults and adolescents with COVID-19 disease in October 2020. [23] Since then, it has gained approval for adults and pediatric patients (aged 28 days and older who weigh at least 3 kg) with positive results of direct SARS-CoV-2 viral testing, who are hospitalized, or not hospitalized and have mild-to-moderate COVID-19, and are at high risk for progression to severe COVID-19, including hospitalization or death. [24]

Treatment does not preclude isolation and masking for those who test positive for SARS-CoV-2.

The first vaccine to gain full FDA approval was mRNA-COVID-19 vaccine (Comirnaty; Pfizer) in August 2021. A second mRNA vaccine (Spikevax; Moderna) was approved by the FDA in January 2022. Additionally, each of these vaccines have EUAs for children as young as 6 months.

Baricitinib (Olumiant), a Janus kinase inhibitor, gained FDA approval for hospitalized adults with COVID-19 disease who require supplemental oxygen, noninvasive or invasive mechanical ventilation, or ECMO. An EUA for children has been issued for baricitinib.

Similar to baricitinib, tocilizumab (Actemra), an interleukin 6 inhibitor, was approved by the FDA for hospitalized adults. An EUA remains in place for children aged 2 years and older.

EUAs have also been issued for vaccines and convalescent plasma in the United States. A full list of EUAs and access to the Fact Sheets for Healthcare Providers are available from the FDA.

Use of corticosteroids improves survival in hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19 disease requiring supplemental oxygen, with the greatest benefit shown in those requiring mechanical ventilation. [25]

All infected patients should receive supportive care to help alleviate symptoms. Vital organ function should be supported in severe cases. [13]

Early in the outbreak, concerns emerged about nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) potentially increasing the risk for adverse effects in individuals with COVID-19. However, in late April 2020, the WHO took the position that NSAIDS do not increase the risk for adverse events or affect acute healthcare utilization, long-term survival, or quality of life. [143]

Numerous collaborative efforts to discover and evaluate effectiveness of antivirals, immunotherapies, monoclonal antibodies, and vaccines have rapidly emerged. Guidelines and reviews of pharmacotherapy for COVID-19 have been published. [26, 27, 28, 29] The Milken Institute maintains a detailed COVID-19 Treatment and Vaccine Tracker of research and development progress.

Searching for effective therapies for COVID-19 infection is a complex process. Gordon and colleagues identified 332 high-confidence SARS-CoV-2 human protein-protein interactions. Among these, they identified 66 human proteins or host factors targeted by 69 existing FDA-approved drugs, drugs in clinical trials, and/or preclinical compounds. As of March 22, 2020, these researchers are in the process of evaluating the potential efficacy of these drugs in live SARS-CoV-2 infection assays. [144]

The NIH Accelerating Covid-19 Therapeutics Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV) trials public-private partnership to develop a coordinated research strategy has several ongoing protocols that are adaptive to the progression of standard care.

How these potential COVID-19 treatments will translate to human use and efficacy is not easily or quickly understood. The question of whether some existing drugs that have shown in vitro antiviral activity might achieve adequate plasma pharmacokinetics with current approved doses was examined by Arshad and colleagues. The researchers identified in vitro anti–SARS-CoV-2 activity data from all available publications up to April 13, 2020, and recalculated an EC90 value for each drug. EC90 values were then expressed as a ratio to the achievable maximum plasma concentrations (Cmax) reported for each drug after administration of the approved dose to humans (Cmax/EC90 ratio). The researchers also calculated the unbound drug to tissue partition coefficient to predict lung concentrations that would exceed their reported EC50 levels. [145]

The WHO developed a blueprint of potential therapeutic candidates in January 2020. The WHO embarked on an ambitious global "megatrial" called SOLIDARITY in which confirmed cases of COVD-19 are randomly assigned to standard care or 1 of 4 active treatment arms (remdesivir, chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir/ritonavir, or lopinavir/ritonavir plus interferon beta-1a). In early July 2020, the treatment arms in hospitalized patients that included hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, or lopinavir/ritonavir were discontinued owing to the drugs showing little or no reduction in mortality compared with standard of care. [146] Interim results released mid-October 2020 found the 4 aforementioned repurposed antiviral agents appeared to have little or no effect on hospitalized patients with COVID-19, as indicated by overall mortality, initiation of ventilation, and duration of hospital stay. The 28-day mortality was 12% (39% if already ventilated at randomization, 10% otherwise). [147]

The next phase of the trial, Solidarity PLUS, continued in August 2021. WHO announced over 600 hospitals in 52 countries will participate in testing three drugs (ie, artesunate, imatinib, infliximab). Patients will be randomized to standard of care (SOC) or SOC plus one of the study drugs. The drugs for the trial were donated by the manufacturers; however, approximate costs are $400/day for imatinib, $3,500 for a dose of infliximab, and $50,000 for a course of artesunate.

The urgent need for treatments during a pandemic can confound the interpretation of resulting outcomes of a therapy if data are not carefully collected and controlled. Andre Kalil, MD, MPH, writes of the detriment of drugs used as a single-group intervention without a concurrent control group that ultimately lead to no definitive conclusion of efficacy or safety. [148]

Rome and Avorn write about unintended consequences of allowing widening access to experimental therapies. First, efficacy is unknown and may be negligible, but, without appropriate studies, physicians will not have evidence on which to base judgement. Existing drugs with well-documented adverse effects (eg, hydroxychloroquine) subject patients to these risks without proof of clinical benefit. Expanded access of unproven drugs may delay implementation of randomized controlled trials. In addition, demand for unproven therapies can cause shortages of medications that are approved and indicated for other diseases, thereby leaving patients who rely on these drugs for chronic conditions without effective therapies. [149]

Drug shortages during the pandemic go beyond off-label prescribing of potential treatments for COVID-19. Drugs that are necessary for ventilated and critically ill patients and widespread use of inhalers used for COPD or asthma are in demand. [150, 151]

It is difficult to carefully evaluate the onslaught of information that has emerged regarding potential COVID-19 therapies within a few months’ time in early 2020. A brief but detailed approach regarding how to evaluate resulting evidence of a study has been presented by F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE. By using the example of a case series of patients given hydroxychloroquine plus azithromycin, Wilson provides clinicians with a quick review of critical analyses. [152]

Ventilator application techniques

Ventilator management and monitoring

Respiratory conditions assessment and management

Prevention

The first vaccine to gain full FDA approval was mRNA-COVID-19 vaccine (Comirnaty; Pfizer) in August 2021. A second mRNA vaccine (Spikevax; Moderna) was approved by the FDA in January 2022. Additionally, each of these vaccines have EUAs for children as young as 6 months. EUAs have been issued for other vaccines.

Avoidance is the principal method of deterrence.

General measures for prevention of viral respiratory infections include the following [13] :

Handwashing with soap and water for at least 20 seconds. An alcohol-based hand sanitizer may be used if soap and water are unavailable.

Individuals should avoid touching their eyes, nose, and mouth with unwashed hands.

Individuals should avoid close contact with sick people.

Sick people should stay at home (eg, from work, school).

Coughs and sneezes should be covered with a tissue, followed by disposal of the tissue in the trash.

Frequently touched objects and surfaces should be cleaned and disinfected regularly.

Preventing/minimizing community spread of COVID-19

The CDC has recommended the below measures to mitigate community spread. [9, 153, 154]

All individuals in areas with prevalent COVID-19 should be vigilant for potential symptoms of infection and should stay home as much as possible, practicing social distancing (maintaining a distance of 6 feet from other persons) when leaving home is necessary.

Persons with an increased risk for infection—(1) individuals who have had close contact with a person with known or suspected COVID-19 or (2) international travelers (including travel on a cruise ship)—should observe increased precautions. These include (1) self-quarantine for at least 2 weeks (14 days) from the time of the last exposure and distancing (6 feet) from other persons at all times and (2) self-monitoring for cough, fever, or dyspnea with temperature checks twice a day.

On April 3, 2020, the CDC issued a recommendation that the general public, even those without symptoms, should begin wearing face coverings in public settings where social-distancing measures are difficult to maintain in order to abate the spread of COVID-19. [9]

Facemasks

In a 2020 study on the efficacy of facemasks in preventing acute respiratory infection, surgical masks worn by patients with such infections (rhinovirus, influenza, seasonal coronavirus [although not SARS-CoV-2 specifically]) were found to reduce the detection of viral RNA in exhaled breaths and coughs. Specifically, surgical facemasks were found to significantly decreased detection of coronavirus RNA in aerosols and influenza virus RNA in respiratory droplets. The detection of coronavirus RNA in respiratory droplets also trended downward. Based on this study, the authors concluded that surgical facemasks could prevent the transmission of human coronaviruses and influenza when worn by symptomatic persons and that this may have implications in controlling the spread of COVID-19. [155]

In a 2016 systematic review and meta-analysis, Smith and colleagues found that N95 respirators did not confer a significant advantage over surgical masks in protecting healthcare workers from transmissible acute respiratory infections. [156]

Investigational agents for postexposure prophylaxis

PUL-042

PUL-042 (Pulmotech, MD Anderson Cancer Center, and Texas A&M) is a solution for nebulization with potential immunostimulating activity. It consists of two toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands: Pam2CSK4 acetate (Pam2), a TLR2/6 agonist, and the TLR9 agonist oligodeoxynucleotide M362.

PUL-042 binds to and activates TLRs on lung epithelial cells. This induces the epithelial cells to produce peptides and reactive oxygen species (ROS) against pathogens in the lungs, including bacteria, fungi, and viruses. M362, through binding of the CpG motifs to TLR9 and subsequent TLR9-mediated signaling, initiates the innate immune system and activates macrophages, natural killer (NK) cells, B cells, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells; stimulates interferon-alpha production; and induces a T-helper 1 cells–mediated immune response. Pam2CSK4, through TLR2/6, activates the production of T-helper 2 cells, leading to the production of specific cytokines. [157]

In May 2020, the FDA approved initiation of two COVID-19 phase 2 clinical trials of PUL-042 at up to 20 US sites. The trials are for the prevention of infection with SARS-CoV-2 and the prevention of disease progression in patients with early COVID-19. In the first study, up to 4 doses of PUL-042 or placebo will be administered to 200 participants via inhalation over a 10-day period to evaluate the prevention of infection and reduction in severity of COVID-19. In the second study, 100 patients with early symptoms of COVID-19 will receive PUL-042 up to 3 times over 6 days. Each trial will monitor participants for 28 days to assess effectiveness and tolerability. [158, 159]